Newly discovered Mars glaciers may help humans settle on the Red Planet one day

'Odd' discovery of channels of ice a welcome surprise for researchers

If humans are to truly become interplanetary settlers, we're going to need to have access to water — a lot of it. But loading it on a rocket would be heavy, and trying to escape Earth's gravity with all that weight would be costly.

That's why space agencies such as NASA and the European Space Agency, as well as planetary geologists, have been looking for sources of water on Mars.

Now, a new paper published in the journal Icarus suggests there is a unique subsurface ice feature in a location that would be optimal for future explorers of the Red Planet.

Ideally, human colonies would be located close to the equator, where it is not only more temperate — in Mars terms — but also easier for a spacecraft to land and take off.

Satellite observations by orbiters around Mars suggest there is an ice sheet in a flat plain called Arcadia Planitia at roughly 35 degrees north latitude. It's a site that both NASA and SpaceX are considering for future human exploration.

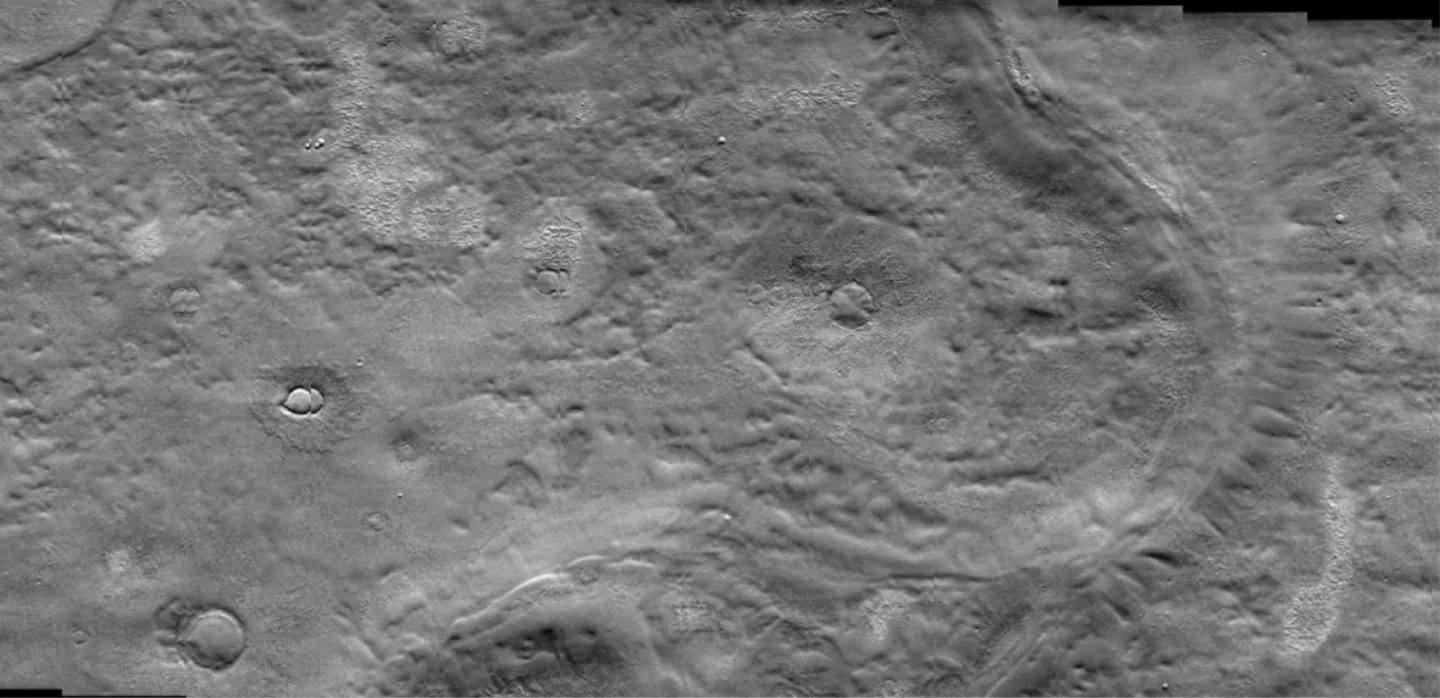

A satellite image of the Arcadia Planitia plain. New research suggests there is a channel of subsurface ice in the flat region that could make it an ideal place for human settlement. (NASA/JPL/Arizona State University)

SEE ALSO: On 'Snowball Mars', immense glaciers may have sheltered ancient microbial life

In this new study, researchers found that it's not just an ice sheet, but a kind of shallow river of ice, similar to what we see in regions of Antarctica.

"When you look closer, you find a lot of characteristics that point to these being glaciers of channelized ice. But what's so odd about it is that it's in a flatline terrain," said Shannon Hibbard, lead author of the paper and a PhD candidate at Western University in London, Ont.

Typically, glaciers would be found either in valleys, gullies or forming around the base of mountains. Instead, this is in a flat area; these types of ice flows weren't expected on Mars.

But it's great news for future human Martians.

"We want to basically land as low, or as close to the equator as we can, and Arcadia Planitia is pretty dang close," Hibbard said.

It's also promising, she said, because the evidence of this massive ice reserve is in a relatively flat area, "and we want to land somewhere flat and boring because that's the safest place to land."

Just how much ice is there? Based on previous research that suggested roughly 13,000 to 61,000 cubic kilometres are below the surface in Arcadia Planitia, the researchers suggest 3.5 to 16 per cent of that volume is the ice channel.

Based on M. Kornmesser's Mars with Oceans simulation, this simulated view shows extensive glaciers covering the planet's surface. (Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser)

MILLIONS OF YEARS IN THE MAKING

Earth and Mars have axial tilts of 23.5 degrees and 25 degrees, respectively. And while Earth's tilt shifts slightly, Mars's tilt can shift by as much as 60 degrees, said Tanya Harrison, a Mars researcher and planetary scientist at Planet Labs, an Earth imaging company, who was not involved in the research.

"At some point in the last few tens of thousands to millions of years, that ice has actually migrated from what [was] the pole to what is today the equator, because the equator becomes the pole," she said.

The findings are particularly exciting to Harrison because they also reveal what Mars was like so long ago.

"Usually when you think of glaciers flowing, they're on the side of a mountain, you know, you have a steep slope that is causing those things to flow downhill. But if you have a flat surface, it's generally kind of hard to get things moving," she said.

"So seeing that maybe we had these ice streams on Mars is really cool, since we've never really documented anything that looked like that before."

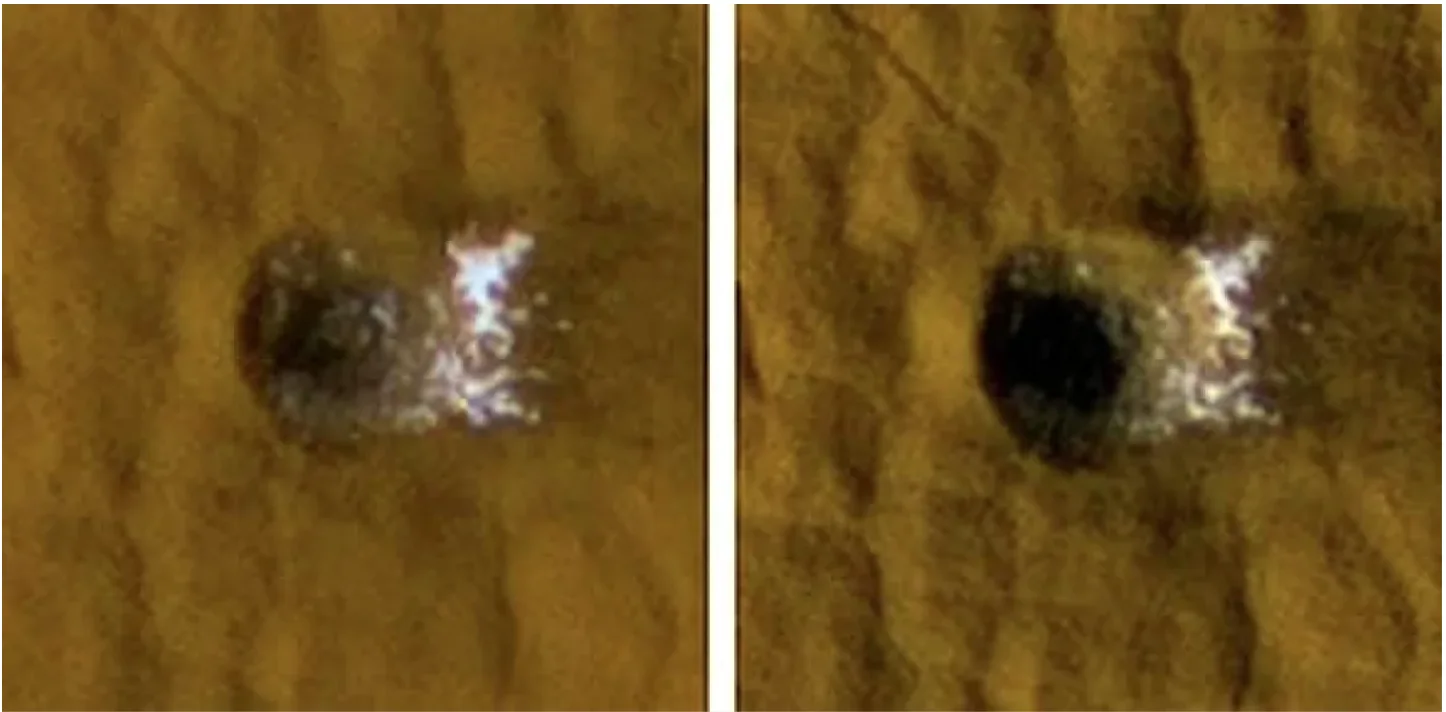

Images of a fresh meteorite crater 12 metres across located within Arcadia Planitia on Mars show how ice faded with time. The images were taken in November 2008, left, and January 2009. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona)

The ice could be used for irrigation, drinking water as well as rocket fuel, which can be made by splitting the hydrogen and oxygen, something that's also been proposed for missions to the moon.

Current radar is able to penetrate from 30 metres to a few kilometres below the surface, said Gordon Osinski, co-author of the paper and director of Western University's Institute for Earth and Space Exploration. But there's more to learn. And it might involve sending a satellite to explore those depths or perhaps a dedicated rover, he said.

"We have a big unknown in the top 10 to 20 metres," he said. "If there is ice there and how much, and of course that's the critical depth, we're not going to go deeper than that remotely to get ice for these human missions."

It's possible Canada will consider playing a role in further research and shallow mapping of the area, particularly after the success of the Canadian radar used on the OSIRIS-REx mission to the asteroid Bennu.

"I really do think there's a need for this mission, and Canada could play a big role because there is the idea that it would be a Canadian radar that would fly on that mission to look at these shallow ice deposits," Osinski said. "So, you know, that's quite exciting to me."

This article, written by Nicole Mortillaro, was originally published for CBC News.